“Every man a king, but no one wears a crown.”

With that slogan Huey Pierce Long Jr. promised to dynamite America’s caste system and pave the rubble with schools, hospitals, and paved highways. To his enemies he was a bayou Mussolini; to his followers he was the first man in living memory who kept the lights on in forgotten parishes. Strip away the legends, good and bad, and you find the father of Southern populism: brilliant, ruthless, and proof that a single determined man can make Wall Street sweat and the White House lose sleep.

Winnfield, Louisiana, produced lumber, Baptist preachers, and every few decades somebody too stubborn to stay. Huey Long, seventh of nine children, was no barefoot redneck; the Longs were respectable, well‑heeled, and politically wired. Poverty never pinched touched him, but the sight of railroad barons squeezing tenant farmers angered his pride. As a teenager he memorized entire textbooks, skipped a grade, and organized a red‑ribbon secret society that dictated playground politics. When the faculty pushed back, he printed flyers denouncing the school’s fourth‑year requirement, plastered it on town fences, and forced the principal’s resignation. Winn Parish had its first taste of Long and they liked it.

“The only difference between the Democratic Party and the Republican Party is, one would skin you from the ankles up and the other from the ankle down.”

-Huey Long

Unable to afford LSU, Long sold encyclopedias door‑to‑door, married Rose McConnell, and talked his way into Tulane Law without a high‑school diploma. One year later he persuaded the state Supreme Court to let him take the bar early. He passed, became a lawyer and “I came out of that courtroom running for office.”

In 1918, Long was elected to the Louisiana Railroad Commission. That same year, he invested just over a thousand dollars, his life savings, into an oil well. Standard Oil blocked his crude from their pipelines, killing the well and costing him everything. That betrayal began his war with Standard Oil that would blossom into a lifelong vendetta.

At twenty‑five Long captured a seat on the Louisiana Railroad Commission and declared total war on monopolies. He slashed utility rates causing telephone and electric bills to drop statewide. He expanded rural rail access pushing rail lines into hamlets mapmakers had ignored. And he attacked Standard Oil banning Mexican crude in state pipelines to protect local wells.

In response Cumberland Telephone sued over rate caps, Long argued the case to the U.S. Supreme Court and won. Chief Justice William Howard Taft called him “the most brilliant lawyer who ever practiced before the Court.” Huey framed the quote and went back to work.

Huey Long jumped into the governor’s race in 1923. He skipped the clubs of Baton Rouge and canvassed the blackwood hamlets the “Old Regular” machine had neglected since Reconstruction. At the time Louisiana’s politics was a one‑party state with rigged elections, 300 miles of paved road, and the nation’s worst literacy rate. Commentators predicted the brash upstart might scrape a few thousand protest votes; instead, he hauled in nearly 72,000, about 31% of the vote, carrying 28 parishes mostly across the dirt poor north of the state. Long placed third, but it was the last election he would ever lose, and it taught him three rules he never forgot:

Speak their dialect, not yours.

Paint your opponent’s donors as the enemy.

If you lose, make the winners bleed in the recount.

The Mississippi Flood of 1927 demolished levees and livelihoods while New Orleans bankers saved themselves. The tragedy was just what Long needed to jump start his next campaign. He drove gravel roads in a Model T fitted with a loudspeaker, denouncing “silk‑stocking liars” who blew dikes to spare Uptown mansions.

Catholic Cajuns, Protestant piney‑woods sharecroppers, Black timber hands, people who had never agreed on religion or race were now in unison. “Every man a king” was less promise than battle cry, and the vote returns proved it: a primary landslide followed by 96% in the general. At thirty-five he became the youngest governor in state history and threw a twelve‑hour inauguration party with free booze and a jazz band. It wasn’t decadence; it was revolution announcing itself with a trumpet.

Once in office, he moved with purpose. He purged opponents from state jobs and filled the ranks with loyalists. Those appointees were expected to kick back a portion of their salaries into his campaign fund. It was corruption, yes, but it was honest corruption. Everyone knew the rules.

He bulldozed legislation through the 1929 session: free textbooks for schoolchildren, road-building programs, public health initiatives. He marched into the legislature uninvited, cornering senators and bullying representatives. When one lawmaker suggested he was unfamiliar with the Louisiana Constitution, Long responded, “I’m the Constitution around here now.”

The Catholic Church balked at his textbook plan. Private schools didn’t want state books. Long said they could have them anyway. Conservative legalists screamed about church and state, but the Supreme Court ruled in Long’s favor.

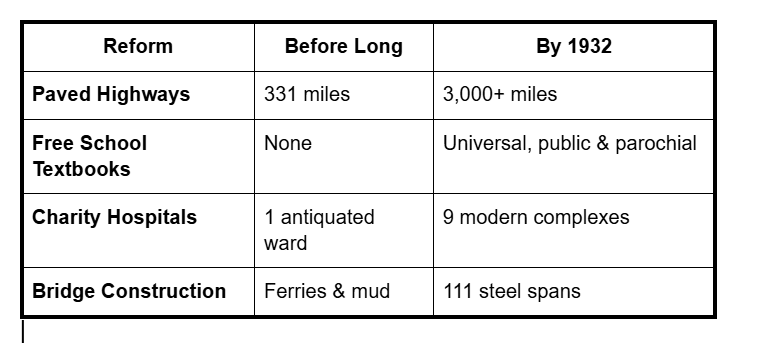

The results of Long’s social programs were obvious…

Long attacked vice dens in New Orleans and when they refused to shut down, he sent in the National Guard with shoot-to-kill orders. Gambling tables were torched, brothels raided, prostitutes hauled out by force. The Attorney General called it illegal. Long responded, “Nobody asked him for his opinion.”

He demolished the old Governor’s Mansion with prison labor and replaced it with a with a bigger, better residence modeled on the White House, so he could be familiar with the architecture when he moved up.

That same year, he proposed a five-cent tax on oil to fund his social programs. The legislature, full of Standard Oil loyalists, pushed back. Long called them out in a radio address, accusing them of being bought. They retaliated by impeaching him. Nineteen charges ranging from bribery to subornation of murder. His own lieutenant governor turned on him. Long responded with what he called a “Round Robin,” a signed pledge from fifteen senators to vote “not guilty” no matter the evidence. That killed the trial dead.

Having survived impeachment he became merciless. He fired opponents’ relatives, supported their challengers in primaries, and told the press, “I used to try to get things done by saying please. Now... I dynamite 'em out of my path.”

In 1930, he ran for U.S. Senate against the establishment’s golden boy, Senator Joseph Ransdell. The newspapers, the church, the businessmen, all lined up against him. He still won, 57 to 43. Voting records showed obvious fraud, with ballots cast in alphabetical order and names like Charlie Chaplin and Babe Ruth showing up. Long didn’t care. His Senate term started in 1931, but he delayed taking the seat to prevent his lieutenant governor from undoing his reforms. When the he tried to take office, anyway, Long had the National Guard surround the Capitol.

Even in the Senate, Long ran Louisiana like a king. He pushed 44 bills through in one night, one every three minutes. His brother Earl doled out state contracts in exchange for loyalty. He expanded LSU, built new dorms, new roads, a medical school, and made the university the pride of the South. He ran night schools that taught over 100,000 adults to read. He capped property taxes, waived the first $2,000 of assessment, and modernized health care. He built more infrastructure in four years than the state had seen in a century.

President Roosevelt called him “one of the two most dangerous men in America,” alongside General MacArthur. FDR froze Long out of federal funding, sicked the IRS on his allies, and tried to smear him through Senate investigations. Long answered with his “Share Our Wealth” plan, which proposed capping fortunes at $100 million, guaranteeing every family $5,000, funding free education, pensions, and public works. By 1935, the movement had over seven million members and 27,000 clubs. His newspaper reached over a million readers. His Senate office received 60,000 letters a week. He was readying a run for president in 1936, but… fate intervened.

On September 8, 1935, Long strutted through the State Capitol after passing a bill gerrymandering Judge Benjamin Pavy out of office. Pavy’s son‑in‑law, Dr. Carl Weiss, stepped from the shadows and fired a .32 pistol into Huey’s abdomen. Long’s Bodyguards riddled Weiss with sixty bullets; Long, bleeding internally, sprinted down three flights of stairs and into a car headed for Our Lady of the Lake Hospital.

Surgeons worked through the night, but a nicked kidney and hidden artery leak went untreated. He died 31 hours later. He was forty-two. Franklin Roosevelt, according to several sources, called the death “a providential occurrence.” In Baton Rouge 200,000 mourners filed past his coffin, while Standard Oil executives reportedly toasted champagne.

Huey Long wasn’t perfect. He was dictatorial, petty, and corrupt. But unlike most men who claw their way to power, he never forgot why he climbed in the first place. Long paved more miles of road in four years than Louisiana had seen in the previous century. He took kickbacks from patronage jobs yet much of the funds went straight into campaign coffers that fueled new hospitals. Long crossed racial and religious lines redrawing the electorate as rich vs. poor. His

Share Our Wealth project jeopardized corporate titans and political dynasties more than any college Marxists ever did.

Judging Huey Long isn’t easy. The Kingfish proved that a single governor armed with a microphone and a list of grievances could lift the people. If his means were blunt, so to were his ends… paved roads, literate citizens, and cheaper light bills, all tangible results that speak for themselves.

Roosevelt sighed in relief the night he died. Ordinary people wept. Huey Long never reached the White House, but the current he generated by the Kingfish would later power the presidential victories of Nixon, Reagan, and Trump.

-TJS

Good article. I don't mind a little bit of corruption when it's in the name of the Greater Good. It's a shame every time we get a man like this, he ends up shot. Every damn time.

Awesome article, thanks for posting.