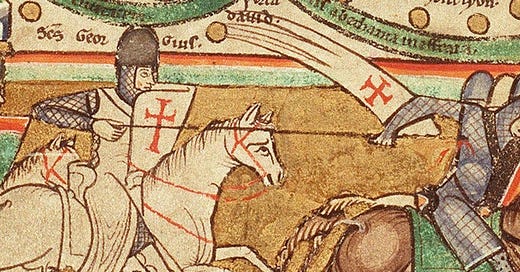

“The knights are dust,

And their good swords are rust,

Their souls are with the saints, we trust.”

- The history of the Knights Templars

The relationship between Christianity and violence is a thread I’ve been unraveling for some time. It’s a complex and often misunderstood topic, particularly in today’s world. When we survey the Christian landscape, it bec…